Healing Our Land—and Ourselves

Noted conservation writer Terry Tempest Williams on building a healthier future

- By Lisa Moore

- Equity and Justice

- Feb 01, 2021

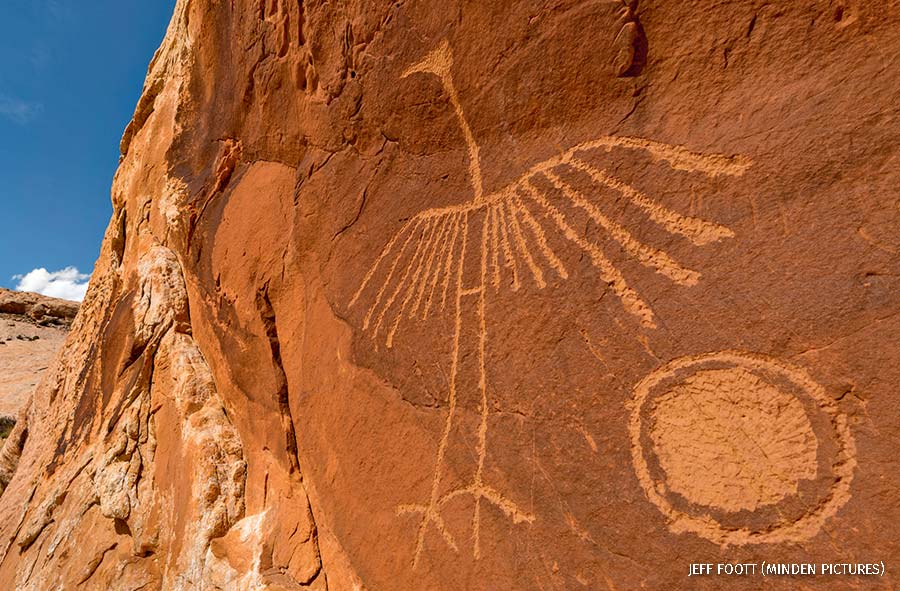

Utah’s red rock country is sacred to Native American peoples.

DURING THE NATIONAL WILDLIFE FEDERATION'S virtual annual meeting last June, award-winning environmental author and activist Terry Tempest Williams shared heartfelt thoughts about the need for America’s conservation movement to become more equitable and inclusive.

Speaking in a Q&A format with NWF board member Brianna Jones Rich, Williams touched on several themes riveting our times, including social unrest over racial injustice, the impact of a brutal health pandemic and the redemptive power of people coming together to bridge divisions for the sake of the planet. During the conversation, Williams made the case that environmental and social issues are inextricably linked—and that the health of the natural world and human beings depends on justice for all.

“This is a time of deep reflection,” she says. “We know it’s political. We know it’s ecological. But I think, fundamentally, it is spiritual. I see this moment as both a reckoning and an awakening at once.”

A Utah native, author Terry Tempest Williams promotes protection of public lands.

Face the past to heal the future

The reckoning begins with an honest look at the history of conservation in the United States. While acknowledging the achievements of great leaders of the past, Williams also notes that North American conservation has been shaped through a lens of “white privilege,” with white leaders determining what constitutes wilderness and how land should be used—and by whom. “As white people, we need to educate ourselves, to speak less and listen more and to be good allies” to the Black, Brown, Asian and Native peoples who have too often been excluded from determining how natural resources should be protected, used and enjoyed.

“I find hope in this engagement,” says Williams. “And it’s essential to the mission of the National Wildlife Federation, which is to unite all Americans to ensure wildlife thrive in a rapidly changing world.”

Such engagement has been a hallmark of Williams’ environmental activism. Speaking from her home in Castle Valley, Utah, she acknowledged the Ute and Hopi peoples, among the original stewards of that desert land, which includes Bears Ears National Monument—sacred to many Native American tribes. In support of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, Williams wrote in opposition to the 2017 federal plan to slash the size of the monument by 85 percent and joined thousands at a protest in Salt Lake City opposing the plan. “If we do not rise to the defense of these sacred lands,” she wrote in the New York Times, “Bears Ears National Monument will be reduced to oil rigs and derricks, shining bright against an oiled sky of obliterated stars.”

In 2017, thousands of people rallied in Salt Lake City to protest a federal plan to shrink the size of public lands, such as Utah's Bears Ears National Monument.

The solace of land

Her passion for land and its power to heal brought Williams to the national spotlight in 1991, when she published Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place. The memoir weaves together the anguish of seeing her mother dying of cancer and the solace Williams found in Utah’s Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. That theme of the healing power of nature suffuses the many books she’s written since—and sustained her while quarantining during the coronavirus pandemic.

At a time when tourism had slowed to a trickle, she’d visit the Colorado River near Moab, Utah. “Instead of seeing a parade of rafts,” she says, “I saw a parade of river otters, beavers, Canada geese, herons, cinnamon teal and peregrine falcons.” Williams acknowledges that immersion in such natural beauty is a privilege that many Americans—particularly people of color—aren’t able to enjoy, either because they don’t have access to natural spaces or they don’t feel safe or welcome in them.

Rectifying this will require what Williams calls promoting “the open space of democracy,” where all people have a voice and are welcomed with respect. “I think with a renewed commitment to communities—both human and wild—with greater diversity and with a commitment to justice for all, we can move past anger to a place of healing.”

Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument is a sacred site for Native peoples, whose ancient petroglyphs adorn its walls.

Erosion and evolution

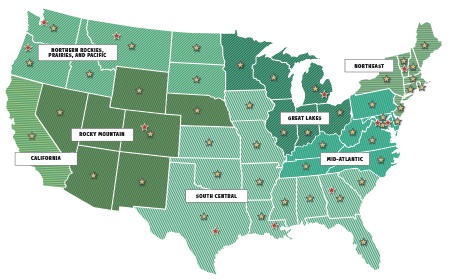

Williams commends the Federation for embracing this challenge and for being a community of diverse state and territorial affiliates and members who promote bipartisan solutions to the nation’s environmental problems.

It’s hard, even uncomfortable, work, says Williams, who sees the environmental movement as “eroding and evolving” at once. “But we can take heart in that,” she says. “The discomfort we feel is our own evolution and a recognition of what we need to do—stand firm on the policies that need to change. I think we each have to look in the mirror and say, ‘If we want the world to change, how do we change ourselves?’”

Are we up to the task? “We have a history of bravery in this country,” says Williams, “and we must call it forward now. I think our future is guaranteed only by the degree of our personal commitment to inclusive justice.” In such a “community of care,” all living beings that share the planet will be better able to thrive.

Lisa Moore is the editorial director of National Wildlife.

More from National Wildlife magazine and the National Wildlife Federation:

Read About NWF's Commitment to Equity and Justice »

National Monuments: More Than Majesty »

Blog: Committing to Equity in a Time of Crisis »