More Than Majesty

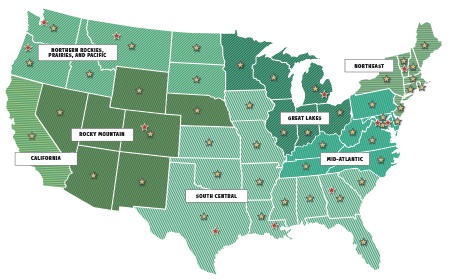

From sea to shining sea—and beyond—the United States’ 157 national monuments are havens for wildlife conservation, outdoor recreation and preservation of indigenous cultures

- Paul Tolmé

- Conservation

- Jun 01, 2018

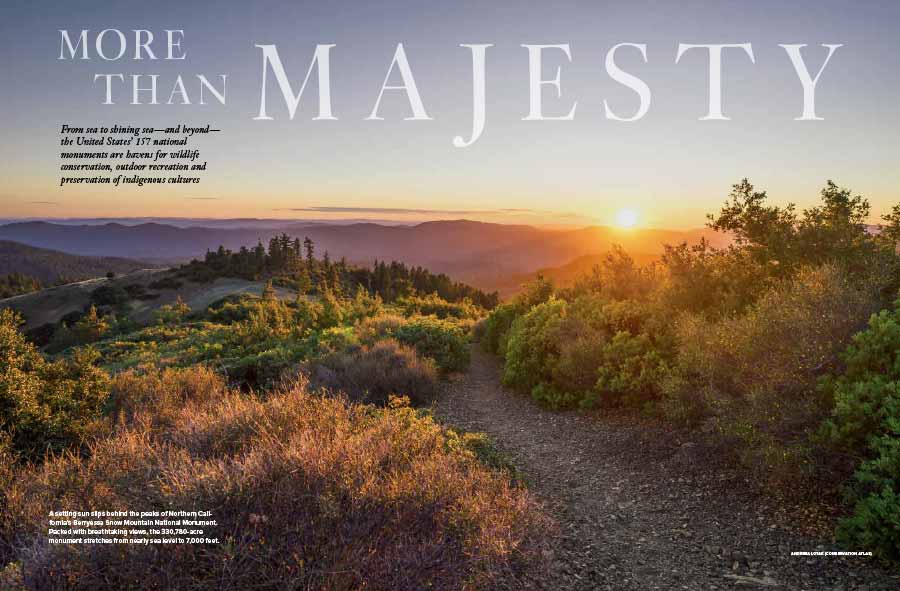

A setting sun slips behind the peaks of Northern California’s Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument. Packed with breathtaking views, the 330,780-acre monument stretches from nearly sea level to 7,000 feet.

TO AVOID COLLIDING WITH SEABIRDS, which fill the air like a blizzard of wings and feathers during daylight, our prop plane landed on a remote Pacific airstrip at night. It was 2010, and we had just touched down on Midway Atoll, one of the world’s greatest seabird rookeries. By day, one can see more than 1 million Laysan albatrosses on the ground and hovering in the air above, the spaces between them filled by frigate birds, boobies, red-tailed tropicbirds, white terns, shearwaters, curlews, petrels and more. It is among a dwindling number of places where visitors still can imagine the world as it once was, when abundant wildlife covered the planet.

Midway is one of 10 islands and atolls sheltered within the 582,578-square-mile Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Created by President George W. Bush in 2006 and expanded by President Barack Obama in 2016, it is one of the world’s largest protected areas. While the monument’s tiny land masses provide vital nesting habitat for more than 20 seabird species—including 70 percent of all Laysan albatrosses—its vast ocean is a sanctuary for corals, fish and other creatures found nowhere else on Earth. Narrissa Spies, a scientist at Hawai‘i’s Kewalo Marine Laboratory, calls Papahānaumokuākea “the endemic species capital of the world.” Researchers exploring its depths with submersible vehicles routinely find animals new to science, from colorful reef fish to octopuses to the world’s largest known sponge (the size of a minivan). “Virtually every time they go down, they discover new species,” Spies says.

My memories of Midway came flooding back in April 2017, when the Trump administration announced it would review the status of Papahānaumokuākea and 26 other national monuments—with the goal of shrinking and opening the protected areas to drilling, mining, grazing, commercial fishing and other extractive uses. Four months later, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke submitted a confidential report to the president recommending reductions in the size of four monuments and making them, along with six others, available for new natural resource extraction. Last December, Trump followed Zinke’s advice by announcing he would dramatically diminish two monuments in Utah: the 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument, which would shrink by 85 percent, and the 1.9-million-acre Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, which would nearly be halved. National Wildlife Federation President and CEO Collin O’Mara called the move “the largest single attack on our nation’s public lands in history.”

In 1906, the Antiquities Act gave U.S. presidents the authority to create national monuments to protect historic artifacts, landscapes and places of scientific value. After signing the act into law, President Theodore Roosevelt created the first monuments, including Arizona’s Grand Canyon, later designated a national park. Since then, both Republican and Democratic presidents have followed suit, and today the United States has 157 national monuments that span from Maine to Alaska to Hawai‘i to offshore territorial waters.

A monument designation allows the government to restrict extractive activities like mining and commercial logging. Such protections make many monuments havens for wildlife. “Cornerstones of our protected public lands, national monuments are home to many of our nation’s most iconic species,” says Mike Leahy, NWF’s senior manager of public lands conservation and sportsmen’s policy. Indeed, every monument under review harbors threatened or endangered species, with Bears Ears alone home to at least 18, including the California condor, Mexican spotted owl and greenback cutthroat trout.

Biologists fear resource extraction in areas Trump wants to cut from Bears Ears may harm resident wildlife. “First, the footprint of development displaces wildlife and permanently alters habitat. From there the impacts ripple out,” says NWF Senior Wildlife Biologist John Kanter, citing a study in Wyoming showing that mule deer avoid energy infrastructure. It’s likely mule deer in Bears Ears “would suffer such impacts,” he adds.

A Laysan albatross nests on Midway Atoll in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. It is one of many seabird species sheltered by the monument, which also hosts a vast diversity of marine life, from tiny coral-reef denizens to humpback whales (above right).

Biodiversity hotspots

President Bill Clinton in 2000 created southern Oregon’s Cascade–Siskiyou National Monument—also on Interior’s hit list—specifically to protect the region’s spectacular biodiversity. Sixteen years later, Obama nearly doubled its size to 114,000 acres at the urging of scientists who said more habitat was needed to preserve rare native species on the margins. “What makes this area special is the multiplicity of so many species of flora and fauna whorling around in one small area,” says Dave Willis, chairman of the Soda Mountain Wilderness Council. The monument’s forests contain Pacific fishers and northern spotted owls, while its wetlands, rivers and streams harbor Oregon spotted frogs, endemic Jenny Creek redband trout and multiple species of endemic springsnails and freshwater mollusks. It is the monument’s butterflies, however, that truly astound—at least 130 species, including the rare Mardon skipper and Johnson’s hairstreak. “Diversity of butterflies equals a diversity of botanical species,” says Willis, who calls the region a “Noah’s ark of botanical diversity.”

A multitude of plant species likewise supports a large variety of pollinators in Grand Staircase–Escalante. Researchers have found more than 640 bee species here—at least 40 new to science. If the administration follows through on plans to shrink the monument, “the risk of losing species before they’re detected is very real,” says former Utah State University graduate student Michael Orr, who identified several new bees in the protected area, including one he named Anthophora pueblo for the ancient cliff-dwelling Pueblo peoples who once lived here.

Offshore, marine national monuments play a particularly vital role protecting diversity. By restricting commercial activities, they allow fish populations to replenish from the ravages of industrial fishing. They also protect delicate coral reefs—among the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet—allowing food webs to rebuild and increasing diversity both inside and outside monument borders. Obama’s expansion of Papahānaumokuākea, for example, was “hugely important because it protects apex predators, including sharks and tuna, that are overfished elsewhere and are essential for healthy marine ecosystems,” says Les Welsh, NWF’s director of conservation partnerships for the Pacific region.

In terrestrial habitats, many species’ survival depends on moving with the seasons to find food, yet human development has decreased wildlife’s ability to migrate across the landscape. “Especially in the West, monuments provide critical migration corridors that will become even more important as climate changes and development increases,” says former NWF public lands fellow Sara Cawley. Oregon’s Cascade–Siskiyou, for instance, protects a narrow, high-elevation biological corridor between the Cascade Range and the Klamath–Siskiyou mountains for species such as the and Pacific fisher. “If you are a critter that needs to get across at high elevation, then you are coming across the Cascade–Siskiyou land bridge,” Willis says.

A cougar sips from a stream in Arizona’s Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Especially in the West, monuments play a critical role providing habitat corridors for animals such as cougars that need to move across the landscape to find water, food or mates. Nestled in a saguaro cactus, great horned owls (above right) are among dozens of wildlife species protected in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert National Monument. Like all monuments, it was created in large part to safeguard the region’s spectacular biodiversity.

Havens for hunting and fishing

With large, intact landscapes crucial to healthy herds of elk, deer, moose and other ungulates, national monuments provide some of the country’s best spots for hunting as well as fishing. “Habitat equals opportunity, and monuments protect that habitat and provide the opportunity to hunt and fish,” explains Aaron Kindle, NWF’s senior manager for western sporting campaigns.

Garrett VeneKlasen, former executive director of the NWF affiliate New Mexico Wildlife Federation, experienced that opportunity while turkey hunting in Bears Ears, which he calls a “highland oasis.” It’s probably the best wild turkey hunting in the West,” he says. “There were turkeys gobbling all around our campground.”

Monuments are epicenters for other outdoor recreation as well. Maine’s Katahdin Woods and Waters, created in 2016 and also on the administration’s review list, features 35 miles of the International Appalachian Trail. The East Branch of the Penobscot River offers some of the state’s best whitewater kayaking as well as calm-water canoeing through stretches with bald eagles and moose. “It’s wild and beautiful and spectacular, and it provides four-season recreation,” says Catherine Johnson, forests and wildlife project director for the NWF affiliate Natural Resources Council of Maine.

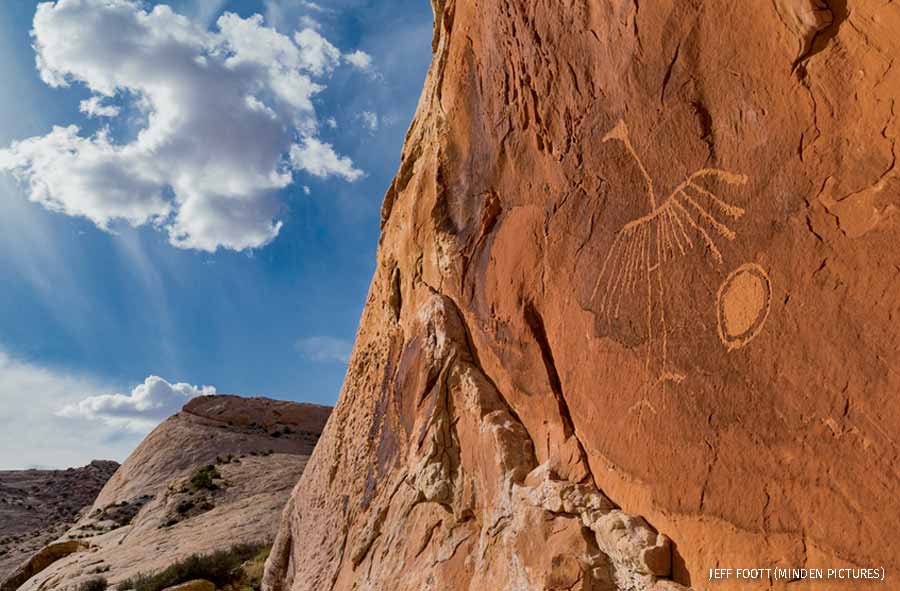

An ancient petroglyph on a rock wall in Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument hints at the cultural significance this protected area has for local Native American tribes. The Trump administration wants to shrink the size of the national monument by 85 percent.

Sheltering cultural treasures

No one, however, would be more negatively impacted by monument cuts than the members of Native American tribes. Bears Ears is among several monuments that have deep cultural significance for tribes. The idea to create it originated with Utah Navajo people, who joined other tribes in the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition to lobby the Obama administration. Willie Grayeyes, a Navajo elder and chairman of the Utah Diné Bikéyah, a nonprofit working with the Navajo and four other tribes to protect Bears Ears, notes that 98 percent of local Native American citizens oppose efforts to shrink the monument. “It is our medicine cabinet, our church and our supermarket,” Grayeyes says. “We have deep ties to the land for ceremonial reasons as well as for subsistence hunting of deer and elk and gathering of wild fruits, medicinal herbs and firewood for heating, cooking and ceremonial uses.”

Near the U.S.–Mexico border, another monument under review, Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks, is vital to Native Americans and to Hispanic communities. “It is where we go to hike and hunt and learn the history of our valley and the people who have lived here thousands of years,” says Gabe Vasquez, Southern New Mexico coordinator for the New Mexico Wildlife Federation. The monument is filled with cultural artifacts, including petroglyphs and ruins of ancient dwellings. In Valles Canyon, visitors can view side-by-side petroglyphs of fish and pronghorn. “I take people there to see that humans have been hunting and fishing on this land for thousands of years before we were here,” Vasquez says. O’Mara calls the administration’s disrespect of tribal culture “the most heartbreaking impact” of its call for monument reductions.

In mid-April, when this issue went to press, it remained unclear whether the order to shrink Bears Ears and Grand Staircase–Escalante would survive several court challenges (including a lawsuit by Native American tribes supported by NWF through an amicus brief) or whether the administration would propose additional monument cuts. Meanwhile, public support for these protected areas is unequivocal: In response to its initial proposal to review the 27 monuments, Interior received nearly 3 million comments, 98 percent in favor of preserving protections.

In New Mexico, supporters of Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks held a town hall meeting last year, with some 650 people filling every seat. “We asked for a show of hands for anyone who opposes the monument, and there was only one person who raised a hand,” Vasquez recalls. “It was a great reminder of how widespread the support in our community is for the monument, from birders to sportsmen to archaeologists to families who hike there.” The story was similar in Hawai‘i. “The proposal to increase Papahānaumokuākea originated with Native Hawaiians,” says Marjorie Ziegler, executive director of the Conservation Council for Hawai‘i, an NWF affiliate that was instrumental in winning support for the monument’s 2016 expansion.

Whatever the outcome of the current controversy, conservationists agree that history will judge the effort to diminish these wildlife sanctuaries as a monumental mistake. “In this increasingly homogenized world, how can we not save some of the few remaining places that are islands of integrity and beauty?” VeneKlasen asks. “In 100 years, people won’t ask why we expanded and created new monuments. They will ask: ‘Why didn’t you make them larger?’”

NWF PRIORITY

Boosting national monuments

A fishing canoe onshore in the Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument hints at the outdoor recreation opportunities afforded by monuments nationwide. For that reason, and because these protected areas are havens for wildlife and preservation of indigenous culture, the National Wildlife Federation has worked for decades to encourage U.S. presidents to create and expand national monuments and to protect these priceless public lands from resource extraction and other threats. To learn more, see www.nwf.org/PublicLands.

Paul Tolmé wrote about the impacts of megafires on wildlife in the June–July 2017 issue.

More from National Wildlife magazine and the National Wildlife Federation:

National Wildlife Federation Members, Supporters Share Experiences, Speak Out for National Monuments »

Keeping Public Lands Public »

Living Legacy »

Celebrating America’s “Great Land” »

Our Work: Public Lands »