Some of America’s most beautiful and iconic bird species have been protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA).

Signed into law in 1918, it is one of the United States’ oldest and most important wildlife conservation laws. Over the past century, the MBTA has played a vital role in saving migratory bird species like the snowy egret, wood duck, and many others from extinction and decline.

History of the MBTA

The MBTA was passed after the massive decline of many birds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries due to overhunting and unregulated commercial trade in bird feathers. The law is a sensible but strong act that currently provides protections for over 1,000 species. It allows for the responsible hunting of many bird and waterfowl species while also protecting birds from harmful industrial activities. For example:

- Power lines cause the deaths of up to 175 million birds a year.

- Communications towers in the U.S. and Canada kill up to 6.8 million birds a year.

- Uncovered oil waste pits account for up to 500,000 to 1 million bird deaths annually.

- Wind turbines kill between 134,000 and 327,000 birds a year.

After the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil spill—which caused the death of more than one million birds—federal officials used the MBTA to ensure BP made recovery payments of $100 million, which is still being used to restore habitat for waterfowl and other birds. This investment in critical recovery efforts would not have been possible without strong protections under the Act.

Act Under Threat

Despite the Act’s significant victories, recent and proposed changes are underway that would roll back the Act’s protections for birds. In December 2017, the Department of Interior reversed decades of protections for birds against many industrial activities by issuing a memorandum concluding that the MBTA does not prohibit any incidental or accidental deaths. In Congress, legislative proposals would permanently change the law to end the Act’s ability to protect birds from incidental, but foreseeable and preventable, deaths from major industrial activities.

Saving the MBTA

Now is not the time to weaken America’s landmark bird protection act. One-third of North American birds are in trouble—a trend that is part of a larger crisis impacting America’s wildlife. The cerulean warbler, for example, has suffered a 75 percent decline between 1996 and 2012, one of the steepest declines of any warbler species. Rusty blackbirds, which breed in freshwater wetlands across boreal Canada and the U.S., have declined 89 percent in recent decades. And the evening grosbeak has declined 92 percent since 1970, the steepest decline of all land birds in the continental U.S. and Canada.

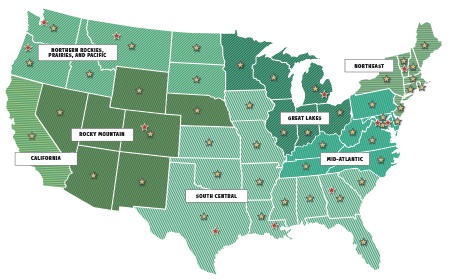

The National Wildlife Federation opposes any legislative or administrative efforts that undermine this Act or its ability to reduce the intentional or incidental loss of birds, and supports the creation of a permit system so the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service can better manage insignificant and unavoidable impacts to migratory birds. Such a permitting system would protect birds and provide clear and consistent expectations to industries and individuals.

Resources

Fast Facts about the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (PDF)