Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972 to protect all "waters of the United States.” Fifty years later, the law is still the main way we are able to safeguard our nation’s waters from pollution and destruction, protecting public health and wildlife habitat.

Before the Clean Water Act, cities commonly dumped raw sewage into America’s rivers. Industrial facilities disposed of their chemical waste in streams, lakes, and oceans. Nearly half a million acres of wetlands were lost annually and by the mid-1980s, more than half the nation’s total wetlands were lost.

Before the Clean Water Act, cities commonly dumped raw sewage into America’s rivers. Industrial facilities disposed of their chemical waste in streams, lakes, and oceans. Nearly half a million acres of wetlands were lost annually and by the mid-1980s, more than half the nation’s total wetlands were lost.

Over the past half-century, the Clean Water Act has brought our waters back to life – turning rivers and lakes from dumping grounds into productive, healthy waterways again. It keeps 700 billion pounds of pollutants out of our waters annually, has slowed the rate of wetland loss, and doubled the number of waters that are safe for fishing and swimming. Levels of metals like lead in our rivers have declined dramatically. Ultimately, the cost to clean our drinking water is lower because the entire system is healthier.

Wildlife benefited too. As water quality improved, fish species rebounded in damaged systems across the country. As fish rebounded, so did many of the species that rely on fish, such as river otters. Learn more about how the Clean Water Act protects our waters here. Para español, por favor haga clic aquí.

Five Decades of Clean Water

The Clean Water Act's Incredible Success, its current limitations and its certain future.

Progress on Clean Water in Jeopardy

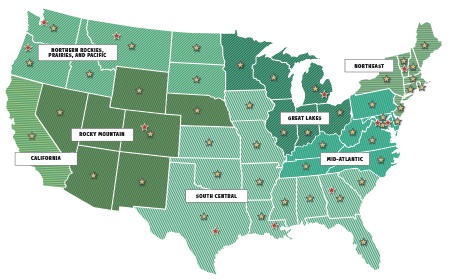

Despite the progress made over the past five decades, too many of our waters still do not meet clean water standards, thanks in large part to a rapidly growing population and ever-intensifying agricultural practices. Now, roughly half of the wetlands and streams across the country are at risk of losing protections under the Clean Water Act. This would have devastating consequences over time as these streams provide drinking water for more than one-third of Americans and the wetlands at risk absorb floods, which protect communities downstream, And of course, these waters are critical for innumerable wildlife species.

On May 25, 2023, the Supreme Court issued a devastating decision in Sackett v. EPA that represents the greatest threat to the nation’s clean water in half a century. The case dealt with the fundamental question of which waters the federal Clean Water Act covers. The decision removed federal protections for over half of America’s wetlands and up to 5 million miles of streams. For additional information on how this decision will impact flooding and drinking water supplies, please click here. For information on how this will impact wildlife, hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation, please click here.

What are the ‘Waters of the United States’?

The definition of “waters of the United States,” or WOTUS, is the keystone of virtually every way the Clean Water Act protects our nation’s waters from pollution and destruction. For three decades, both the courts and the agencies responsible for administering the Clean Water Act interpreted this phrase to broadly encompass all streams, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and coastal waters.

However, in two decisions – Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (2001) and Rapanos v. United States (2006) – the Supreme Court threw into question the safeguards for many wetlands and streams across the country, with the late Justice Scalia calling on the Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers to clarify the issue via the federal rulemaking process.

In 2015, under the Obama Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers finalized a rule, known as the “Clean Water Rule,” which restored protections to most waters– with a few exceptions, such as isolated wetlands.

The Trump administration repealed the 2015 rule and in 2020 replaced it with an extremely narrow definition of “waters of the United States” that removed protections from roughly half of the nation’s streams and wetlands. The 2020 rule was swiftly struck down in court, with the judge citing the rule’s “fundamental, substantive flaws” and the risk of “serious environmental harm.”

However, during the brief period that the 2020 rule was in effect, it became clear this type of narrow interpretation of the “waters of the United States” would have a devastating effect on the nation:

- In desert regions, nearly all streams and arroyos were left unprotected, with devastating consequences for drinking water supplies. For example, the rule invalidated the federal permits controlling the levels of mercury and PCBs running off the heavily contaminated grounds of Los Alamos National Laboratory and ultimately into Santa Fe’s drinking water supply.

- In Georgia, the rule allowed the construction of a mine on 400 acres of wetlands immediately adjacent to Georgia’s Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge – an internationally recognized wetland.

- Many coastal wetlands were not protected by the rule, leaving tens of millions of Americans who live in coastal counties at greater risk from hurricanes. Furthermore, the rule also removed protections from many prairie wetlands. If the rule had remained in place, the flood-prone Houston region could have seen its remaining storm-absorbing prairie and coastal wetlands paved over at an ever faster rate, leaving the region at even greater risk.

What's the Solution?

As we celebrate fifty years of the Clean Water Act, we have a critical opportunity to restore and strengthen protections for clean water across the country.

The Biden Administration has already taken an important step to restore longstanding Clean Water Act protections for small headwater streams and wetlands by essentially returning to the pre-2015 practice, where the U.S. Army Corps makes a case-by-base determination if a stream or wetland is protected. For more detail, read joint comments from the National Wildlife Federation and 37 of our affiliates on this rule.

The Administration is currently crafting a new rule defining the “waters of the United States.” The agency should move swiftly to develop a clear, science-based rule that will cover our nation’s waters from small mountain streams to our immense coastline.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court has announced that it will take up a case that could affect the scope of wetlands protection, with a decision likely to be issued in the fall of 2022.

To learn more about events and other ways to celebrate the Clean Water Act’s 50th anniversary, visit the Clean Water for All Coalition’s webpage. Add your voice in support of strong clean water protections. Sign the petition!